Madam Marie Curie: A Radiant Legacy of Science, Sacrifice, and Inspiration

Maria Salomea Skłodowska-Curie (7th November 1867 – 4th July 1934) simply known as Marie Curie, was a Polish and Naturalised-French (1895-1934) physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity. The early life and education of Marie Curie were marked by resilience, intelligence, and a determination to overcome the social and political obstacles of her time. Maria Salomea Skłodowska-Curie was born on November 7, 1867, in Warsaw, Congress Poland, Russian Empire (now Poland). She was the youngest of five siblings in a family of educators.

Her parents wee both teacher and they fostered a passion for knowledge among their children. They were Polish nationalist and the time was under the Russian rule, as a result they faced economic hardships and repression. Despite these obstacles in life, they cultivated a home filled with a thirst for knowledge and a sense of cultural identity. Curie’s life was marked by her relentless dedication to science, which led her to become the first person to win two Nobel prizes in two different scientific fields – Physics and Chemistry.

Family and Early Education:

Władysław Skłodowski, Marie Curie’s father, taught mathematics and physics in a school, while her mother, Bronisława operated a well-respected girls’ boarding school. Both parents were passionate about education. But, due to political affiliations Władysław lost his job, and due to health problem Bronisława had to close her school, resulting financial crisis in family. Unfortunately, Bronisława died from tuberculosis, at that time Maria was just 10 years old. Her eldest sister Zofia had died of typhus a few years earlier. Young Marie was deeply impacted by these losses and turned to her academics as a coping mechanism.

In secondary school, Marie attended a gymnasium for girls in Warsaw, where she graduated with top honors. At that time, in Poland, the higher education was not an option for women, as a result she was not allowed to get admission at the University of Warsaw. In Warsaw, Marie joined the “Flying University” an underground organization that supported the Polish culture and gave the women access to the academic education while the Russian government prohibited it. Here, she studied a rage of subjects, which ignite her further interest in the science.

Maria Skłodowska-Curie Museum, at 16 Freta Street in the New Town district, Warsaw, Poland

The Dream of Studying Abroad:

In order to pursue her studies in Physics and Mathematics, Marie Curie dreamed of attending a world-renowned university, but due to financial constraints and political obstacle pursuing her dream was difficult. So she entered into deal with her sister Bronisława, who also wanted to study medical. According to the agreement, Marie would work as a governess and tutor to support education of Bronisława in Paris, and in exchange, Bronisława would support Marie’s academic pursuits once Bronisława completed her studies and found employment.

From the age of 17, Marie started to work as governess. For several years Marie Curie worked as a governess in Poland, using limited free time to study science on her own. She remained focused on her goal despite her time as a governess was difficult. She saved as much as possible, and studied physics and mathematics in her spare time. Finally in 1891, at age of 24 she moved to Paris.

Higher Education in Paris:

After moving to Paris, she got admission at the University of Paris, known as the Sorbonne. The change was challenging for her because she had to deal with a language barrier, financial issues, and the adjustment to live abroad. The living condition of Marie was extremely modest. She often skipped meals to save money, and focused intensely on her studies. She excelled academically in spite of these obstacles. At first she lived in the home of her sister who was now married, but later opted to rent a little attic closer to the university. She often stayed at the heated library until closing rather than spend the evening in her unheated room. Her earlier education had been insufficient so there was a lot of catching up to do. Despite the difficulties, Marie marveled at her freedom.

“It was like a new world opened to me, the world of science, which I was at last permitted to know in all liberty” – Marie Curie

In 1893, she graduated first in the class with a degree in physics and second in her class with a degree in mathematics the following year.

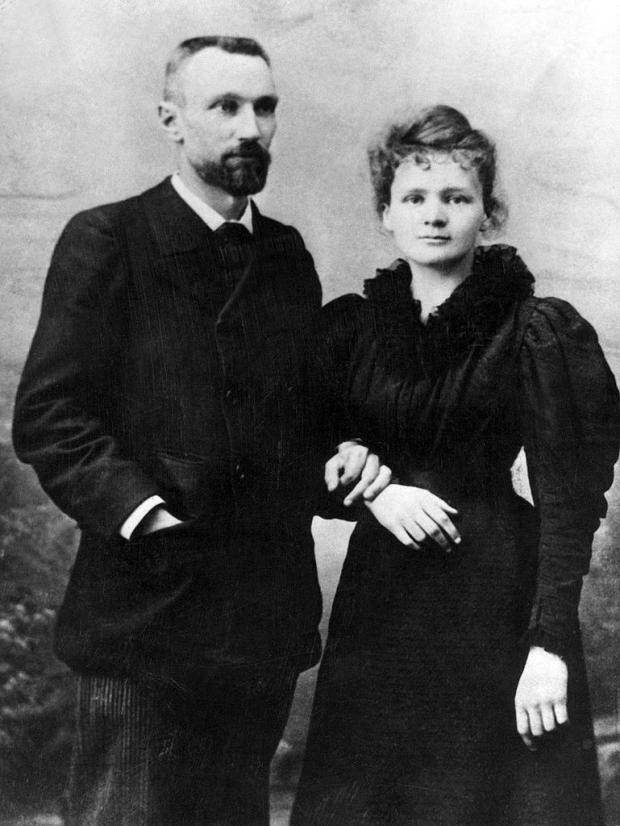

Meeting with Pierre Curie:

Curie’s remarkable scientific career began with her commitment to her studies in Paris. Her time at the Sorbonne was a period of intellectual growth. There she made valuable connections in the scientific community, including her future husband, Pierre Curie, a physicist whose research in magnetism would complement her own interests in radioactivity.

She planed on returning to Poland but Pierre Curie came into her life. He was eight years older that Marie and a well-known physicist who was educated by his father in his teens. They were introduced by a mutual friend who knew Marie needed a lab space for her research and Pierre headed a laboratory at the School of Industrial Physics and Chemistry where engineers were trained. Marie would say of Pierre: “He had dedicated his life to his dream of science: he left the need of a companion who could live his dream with him.” And he hoped that companion would be her. But Marie turned down his marriage proposal since her plan was to return her native country. How ever she learned that it could not be possible to start a career in Poland. When she went back to visit her family during summer break in 1894, Krakow University denied her a job of a professor because she was a woman. Pierre convinced her to come back to Paris to pursue a PhD. She also insisted that he, too, get his doctorate, which he did, pioneering research on magnetism. Finally in 1895, they married at the town hall in Sceaux in the suburbs of Paris. Partners in life and science. On her wedding day, Marie wore a dark blue outfit that would become her trademark in the laboratory. They bought bicycles with the money they received as a wedding gift. In 1903, Marie Curie was awarded by Doctor of Science degree from Sorbonne.

Groundbreaking Research and Discoveries:

Our knowledge of atomic science was revolutionized by Marie Curie’s pioneering work on radioactivity, which also set the stage for further advances in nuclear physics, chemistry, and medicinal therapies. She received Nobel Prizes in Chemistry and Physics for her groundbreaking discoveries, which also represented significant turning points in her career. Here’s a closer look at her contributions and the impact of her work.

Discovery of Radioactivity:

Curie started her research as part of her PhD thesis in Physics, a field that had rarely been studied by women at that time. In 1896, physicist Henri Becquerel, discovered that uranium emitted rays that could expose photographic plates, similar to X-rays. Curie was so inspired by this work that she chose to study these mysterious rays as her research focus.

Curie’s experiments involved measuring the electric current that certain minerals, like uranium, could generate. Through rigorous testing, she realized that the intensity of the ray solely depends on the quantity of uranium, not the mineral composition, which concluded that the emissions were an inherent property of the atoms themselves.

This led her to coin the term “radioactivity” to describe the phenomenon. Curie’s work suggested that atoms were more complex that previously believed and could release energy in the form of radiation.

Discovery of Polonium and Radium:

Marie Curie with her husband Pierre Curie began studying other minerals to see if they contained radioactive elements. In 1898, the Curies made an astonishing discovery. After Testing the mineral pitchblende, which was far more radioactive than uranium alone, they hypothesized that it contained additional, unknown radioactive elements.

In July 1898, they announced the discovery of a new element, polonium, named after Marie’s native Poland. Just a few month later, in December 1898, they discovered radium, a second radioactive element. The Curies successfully isolated small amounts of radium chloride in 1902, despite the challenging process of processing tons of pitchblende and working in primitive lab conditions.

Contributions to Atomic Theory:

Marie Curie’s work fundamentally altered our understanding of the atom. At that time, scientists believed atoms were indivisible. However, her research showed that atoms could decay and emit energy, revealing their unstable nature. This discovery directly influenced the development of quantum mechanics and nuclear physics, two fields that have since transformed science and technology. Curie’s research provided a foundation for later studies on atomic structure and eventually led to the development of nuclear energy.

Practical Application: Medicine and Beyond:

One of the most significant applications of Curie’s discoveries has been in medicine, especially in the field of oncology. The radiation therapy, a treatment of cancer, was developed by the ability to emits radiation be Radium. To understand the potential of radium in treatment of tumors Curie worked with doctor during her lifetime. Since Curies realized that radium might be used to view inside the body and diagnose injuries, their discovery also let to the way for creation of X-ray machine.

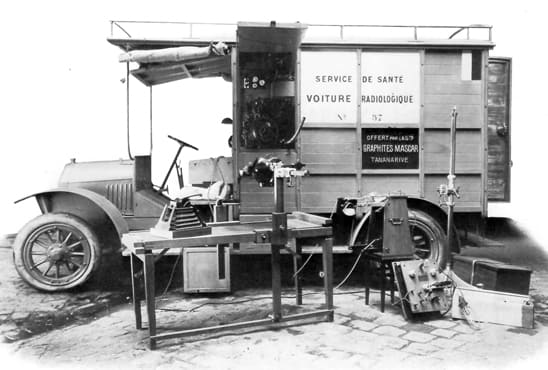

During World War I, to assist the doctors, Marie Curie personally organized and equipped mobile x-ray unit on the battlefield. This mobile radiography unit was known as “petites Curies”. These are used to locate fracture and shrapnel in wounded soldiers, saving countless lives.

Nobel Prizes and Rumors:

In 1903, Marie and Pierre Curie, along with Henri Becquerel, were awarded the Noble Prize in Physics for their work on radioactivity. French academic originally proposed that only Pierre and Becquerel receive the prize. Leaving Marie out.

However a sympathetic member of the nominating committee, Swedish mathematician Gösta” Mittag–Leffler altered Pierre to the situation. He insisted that his wife share the honor. Marie Curie became the first women to win a Noble Prize, an unprecedented achievement at that time. She and her husband were too busy with their research to accept the award in person in Stockholm. Pierre was also sick at that time, suffering from pain and fatigue. They had no idea at that time that the radiation could be detrimental to their health. Unfortunately, in 1906 Pierre Curie died in an accident, leaving Marie to continue their work. During this time, Marie was offered his academic post at the Sorbonne, she accepted that instead of accepting the widow’s pension. She became the first female professor in France. To attend her debut lecture, hundreds of people waited in line outside the institution.

In 1911, Curie was awarded a second Noble Prize in Chemistry for her discovery of polonium and radium and for her research on the properties of radium. This made her the first and to this date, the only person to win Noble Prize in two different scientific fields. But there was a buzz around her, which was not great. Her affair with her husband’s former student, physician Paul Langevin, was widely reported by the French press. Paul Langevin was married but put as a distance from his wife. They called her a home wrecker and even gave warning that it might be best if she did not pick up the Prize in person. As a result, she went through a deep depression.

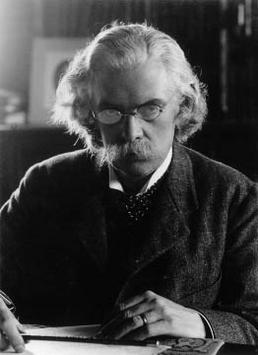

She was slowly pulled out from that mental situation by the support of a fellow scientist. In 1911 Solvay Conference, Albert Einstein struck up a friendship with Curie. During that dark period, Einstein wrote a letter to encourage her: “I am impelled to tell you how much I have come to admire your intellect, your drive, and your honesty….” He also added “simply do not read that hogwash…” to tell her not to pay attention to the stories in the press. So finally, Marie Curie went to Stockholm and received her second Nobel Prize and the scandalous headlines ultimately faded away.

Tragedies:

Zofia Skłodowska (nicknamed Zosia) was the elder sister of Marie Curie. At the age of 14, Zofia died from typhus, at that time Marie was only eight years old. She contracted the disease in 1876, likely from an infected boarder who lived in Skłodowska family’s home, which was a common practice that time to supplement family income. This loss had a profound effect on her.

Bronisława Skłodowska was Marie’s mother. She was suffering from tuberculosis, which was a widespread and often fatal disease at that time. Despite her illness, Bronisława continued to work in education, running a girl’s boarding school to support the family. Her tuberculosis gradually worsened, and she passed away in May 1878, when Marie was just ten years sold. The loss of her mother, coming so soon after her sister’s death, was devastating for young Marie, contributing to her early resilience and independence.

Władysław Skłodowski was Marie’s father, who was a teacher of mathematics and physics. He lived longer than his wife and daughter, passing away in 1902. Władysław continued to support and encourage Marie’s and her siblings’ education despite their family’s financial difficulties. His commitment to learning and intellectual development played a significant role in Marie’s educational ambitions and her eventual success.

In April 1906, on a rainy day, Pierre was runover by a horse and carriage while walking the Rue Dauphine, he slipped on the wet cobblestones and fell, and the cart’s wheel ran over his head, killing him instantly. The most difficult time in her life would be after the death of her husband. This death was a devastating loss for Marie, both personally and professionally. They had a strong partnership, not only as husband and wife but also as scientific collaborators. In 1911, when she put herself forward for a vacant seat, her membership was rejected by the French Academy of Sciences which was the gathering place for prominent scientists. Edouard Branly, a physicist and inventor, was chosen over her. It was suspected that because she was a woman and an immigrant, that’s why it was happened with her.

Contribution during World War I:

She moved her cache of valuable radium to a bank vault in Bordeaux, the new capital of southwestern France, as German forces headed towards Paris. She also tried to sell her two gold Noble prize medal to help the war effort but the national bank refused to accept them. She would use her prize money to purchase war bonds, but she felt that this selflessness was insufficient. She was committed to saving French soldiers’ lives by applying her research.

During World War I, Marie Curie played a crucial role in advancing battlefield medical care by pioneering the use of mobile X-ray units to help treat wounded soldiers. As the war broke out in 1914, Curie saw that soldiers on the front lines were suffering from injuries that could be better treated if doctors could locate bullets, shrapnel, and fractures within their bodies. X-ray technology, which had been developed in the late 19th century, could make this possible, but few hospitals near the battlefields had access to X-ray machines.

Curie developed mobile radiography units, known as “petites Curies” (little curies) to improve the battlefield surgeries, which were basically a car equipped with a X-ray machines and a dynamo for electricity generation. Around 20 mobile units were equipped funded by the French government and wealthy friends. Over 200 stationary X-ray installation were established near the hospital and field stations. Curie personally drove one of these mobile units to the front and trained medical professionals in X-ray equipment.

Curie trained 150 women as radiology technicians to operate mobile X-ray units, creating a skilled corps of operators. She also conducted extensive training in radiological techniques and safety, helping thousands of soldiers make informed decisions in treating injuries.

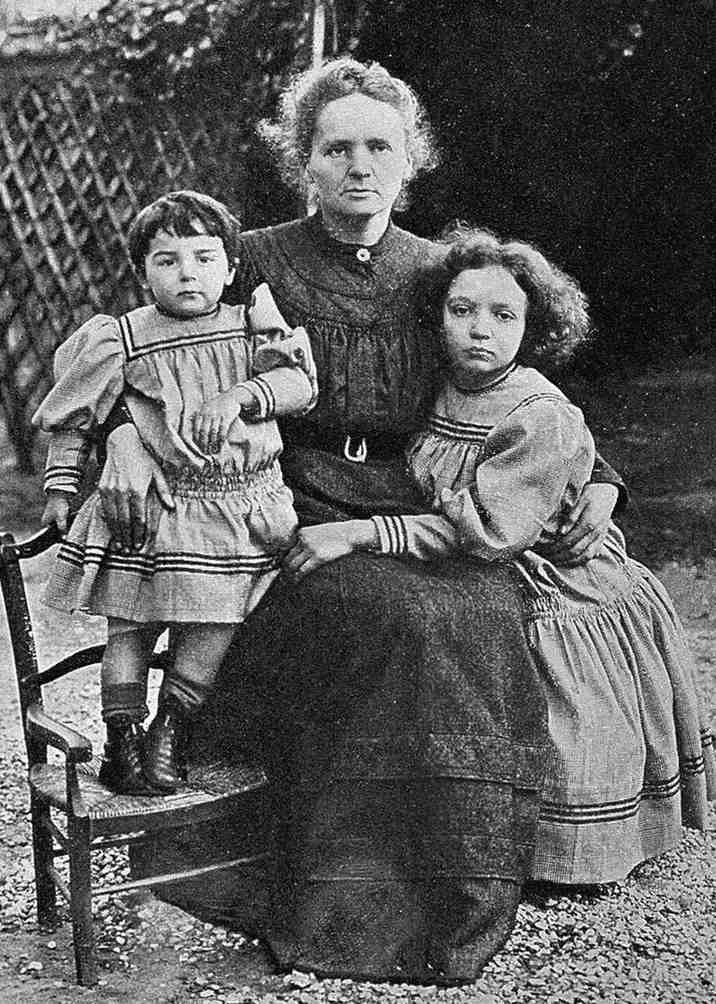

Her intense wartime efforts drained her physically and financially. She and her daughter Irène, who was only 17 at the time, often worked together in field hospitals and shared in the heavy responsibilities. Irène, inspired by her mother’s dedication, would go on to become a Nobel-winning scientist herself.

By the end of the war, Curie’s efforts are said to have saved the lives of millions of troops, but may have cost her own. She was aware that, her health would be at risk due to the excessive X-ray exposure. However, there was no time to enhance safety practices. While she was becoming more and more well-known outside, the French government never officially recognized her humanitarian work. In order to support her research work, U.S. President Warren Harding invited her to the White House in 1921 and gave her a gram of radium as a gift.

It seems that the French government was embarrassed because they did not give her any special treatment. They therefore offered her the Légion d’Honneur or the Legion of Distinction, the nation’s highest honor, prior to that journey to Washington DC. However, she refused that.

During her later years, she headed the Radium Institute – later the Curie Institute in Paris. And opened another in Warsaw, where her sister Bronya became the director. Both remain major research institutions to this day. Radium Institute in Warsaw now known as the Maria Skłodowska-Curie Institute of Oncology.

By that time, she was already in poor health condition. Curie passed away at the age of 66 on July 4, 1934, in a sanatorium in the eastern French town of Passy. A year latter she was not around to witness her daughter Irène share the Nobel Prize in Chemistry with her husband, physicist Frédéric Joliot, for creating new radioactive elements artificially.

Love for Motherland Poland:

Indeed, Marie Skłodowska Curie held her Polish heritage close to her heart, even after becoming a French citizen. Her pride in her Polish identity was a significant part of her life, influencing both her personal and professional decisions. She maintained the use of both her maiden name, Skłodowska, and her married name, Curie, as a testament to her roots.

Marie passed on this connection to her homeland to her daughters, Irène and Ève, by teaching them the Polish language and encouraging their interest in Polish culture. She also took them on regular visits to Poland.

In 1898, when Marie and her husband, Pierre Curie, discovered a new element, she named it polonium in honor of her native Poland, which at the time was partitioned and not recognized as an independent nation. This act was both scientific and symbolic, as it drew international attention to Poland’s political plight while establishing Marie’s legacy as a Polish patriot.

Conclusion:

Marie Curie’s research on radioactivity is one of the most influential scientific achievements of all time. Her work has had lasting effects on numerous fields, from nuclear physics and chemistry to medicine and medical imaging. She established a legacy that inspired women to pursue careers in science, challenging societal norms and proving that dedication and perseverance could overcome significant barriers.

In Sceaus, a suburb of Paris where she was married, Curie was laid to rest alongside her spouse. In 1995, both were relocated to Panthéon in Paris, which is the final resting place of numerous notable French figures, including Voltaire, Rousseau, and Victor Hugo. The first woman to receive recognition in the Panthéon for her own achievements was Curie. Her remains were placed in a coffin lined with over an inch of lead since they were still radioactive. Even now, her documents remain radioactive. Wearing protective clothing and signing a waiver are requirements for anyone wishing to inspect them. The only thing that could top Curie’s tireless efforts was her struggle to get over the obstacles that stood in her way of becoming one of the greatest scientists of all time. Her work ethics was just as outstanding as her work itself.