It was 5:00 p.m. on Thursday, January 7, 1610. Galileo Galilei stood in his garden in Padua, northern Italy. In his hands, he held a telescope which he recently built by himself. That night, he had decided to try something, no one else has done before: he was going to point his telescope toward Jupiter.

Galileo had no idea that this single act would change the world forever. With a simple turn of his wrist, he was about to open a new chapter in science. By looked at Jupiter, he would begin to settle an age-old question about our place in the universe.

But what brought Galileo to this moment? What journey led him to this night, standing alone under the dark sky, determined to learn more than anyone before him?

Early Life, Family and Education:

On February 15, 1564, Galileo Galilei was born in Paris (Which was a part of the Duchy of Florence), Italy. He was the first of the six children of Vicenzo Galilei and Giulia Ammannati. Vincenzo was a well-known lutenist, composer. Giulia was the daughter of a successful merchant. Vincenzo and Giulia had married in 1562 when Vincenzo was 42 and Giulia was 24. Galileo learned to play the lute well and likely inherited his father’s questioning attitude toward accepted beliefs. Galileo grew up during a transformative period in science, art, and thought known as the Renaissance.

Three of Galileo’s Five siblings survived their childhood. The youngest of them was Michelangelo, who also became a lutenist and composer, like their father. Michelangelo was struggled financially throughout his life, as a result he often relied for money on Galileo. He wasn’t able to pay his share of the dowries their father had promised for their sisters, which led to tension with their brothers-in-law, who even tried to take legal action to get the money owed. Michelangelo also borrowed money from Galileo to fund his musical projects and travels. These financial pressures may have pushed Galileo to invent things that could earn him extra income.

When Galileo was eight years old, his family moved from Pisa to Florence. However, he stayed behind in Pisa for two years under the care of family friend Muzio Tedaldi. At age of ten, Galileo moved to Florence from Pisa to join his family. There he began studying with a teacher named Jacopo Borghini. During the time from 1575 to 1578, Galileo received education in logic at the Vellombrosa Abbey, located about 30 kilometres southeast of Florence.

In 1581, when he was 17, Galileo enrolled at the University of Pisa to study medicine, as his family hoped he would become a doctor. However, Galileo found himself far more interested in mathematics and physics than in medicine. He spent time learning from the works of classical mathematicians, like Euclid and Archimedes, which deepened his love for these subjects. With the encouragement of a family friend and mathematician, Ostilio Ricci, Galileo began to focus more on math, exploring concepts that were rarely questioned at the time.

After three years, he left the university without completing his degree, choosing instead to pursue his studies in mathematics and philosophy independently. This decision would set him on the path to becoming one of history’s most influential scientists, as he began testing ideas about motion, physics, and the nature of the universe that would challenge the scientific beliefs of his time.

Marriage Life:

Galileo Galilei and Marina Gamba had three children together, although they never married. Their first daughter, Virginia, was born in 1600, and second daughter, Livia, was born in 1601. Both daughters went to live in a convent near Florence in 1613. They stayed there for the rest of their life although their father Galileo faced challenges with the Catholic Church. Galileo was especially close to Virginia, who became Sister Maria Celeste in the convent. She helped her father from the convent by baking, sewing, and doing other tasks for him. In return, Galileo sent food and supplies to the convent, which struggled with poverty.

Vincenzo, Galileo’s son, was born in 1606. He studied medicine at the University of Pisa, latter married into a good family, and eventually settled in Florence.

Story Behind Galileo’s name:

Galileo usually went by his first name alone, which was common in Italy at the time. His name, “Galileo,” and his family name, “Galilei,” both came from an ancestor, Galileo Bonaiuti, a respected doctor and professor in 15th-century Florence. This ancestor was buried in the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence, the same place where Galileo himself would be buried about 200 years later.

Sometimes, Galileo signed his name as “Galileo Galilei Linceo” to show his membership in the Accademia dei Lincei, an elite scientific group. In Tuscany, it was also a tradition for families to name their eldest sons after the family name, so Galileo may not have been named specifically after his ancestor. The name “Galileo” means “of Galilee” in Latin.

Now come to the question, What journey led Galileo to that night, standing alone under the dark sky, determined to learn more than anyone before him?

It was the early 17th century, a time of great changes. In India, the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan had begun building the Taj Mahal. The Romanov family had just taken control of Russia, a dynasty that was going to last over 300 years. Meanwhile, in Europe, the powerful Spanish Empire started to show signs of weakness. And in a small corner of Europe, a new nation was rising fast: the Dutch Republic.

The Dutch Republic, formed in 1608, was booming with trade, invention, and ambition. Dutch merchants dominated the seas, and scientists and inventors were filled with curiosity and drive. Lens-making skills were improving quickly, and it was only a matter of time until someone experiments with stacking two lenses together. In a small coastal town called Middleburg, a lens-maker named Hans Lippershey did that. On October 2, 1608, he filed a patent for a “perspective glass” — the first telescope — a device that lets people see distant things up close.

Word of this invention spread fast across Europe, sparking excitement among scientists and thinkers. Soon, news of the telescope reached to Galileo Galilei, a 45-year-old Italian mathematician and professor.It’s June 1609, and Galileo visited Venice when he hears about this “Dutch perspective glass” that can magnify three times. Inspired, Galileo rushed back to his workshop in Padua and started building his own telescope. Within days, he designs a version, and by August 25, 1609, he improved it enough to magnify eight times. He demonstrated his telescope to Venetian leaders, who quickly saw its potential for spotting enemy ships. They were impressed, and Galileo gained their support.

But Galileo’s interest was not in military use. He wanted to point his telescope toward the sky. Soon, he build an even more powerful telescope with 20-times magnification, allowing him to see far deeper into space than ever before. He first pointed it at the moon and saw craters, valleys, and mountains, revealing a rough landscape that no one expected. He then turned to the Milky Way and discovers it’s made up of countless stars.

On the night of January 7, 1610, Galileo pointed his telescope at Jupiter. At around 5:00 p.m., he noticed three bright spots near the planet, two on one side and one on the other. Over the next several nights, he watched these “stars” moving, and he realizes they were not stars at all — they were moons, orbiting Jupiter just as our moon orbits Earth. By January 15, he confirmed that there are four moons around Jupiter. Today, we know them as Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

This discovery changed everything. For centuries, people believed that everything in the universe revolved around Earth, but here was proof that other objects could orbit a planet. Galileo had just provided evidence that the Earth is not the center of everything. He quickly published his findings in a book called Sidereus Nuncius, or The Starry Messenger, in March 1610. The book sold out across Europe and causes a sensation, giving new life to the idea that Earth orbits the sun — the heliocentric model.

Galileo’s simple decision to point a telescope at the night sky had set off a scientific revolution. Though he was going to spend the rest of his life defending his discoveries against the Church, his work opens the floodgates for a new era of scientific exploration. With his telescope, Galileo has forever changed humanity’s view of the universe.

Leaning Tower of Pisa Experiment:

The story of the Leaning Tower of Pisa experiment is one of Galileo’s most famous legends. According to this tale, in the late 1500s, young Galileo, then a professor at the University of Pisa, was determined to prove an idea that went against centuries of teaching. At the time, people believed Aristotle’s idea that heavier objects fall faster than lighter ones. To challenge this, Galileo supposedly took two metal balls of different weights and climbed the Leaning Tower of Pisa. In front of curious onlookers, he dropped both balls from the top of the tower. To everyone’s surprise, the two balls hit the ground at the same time. This dramatic demonstration is said to have shown that all objects fall at the same rate, regardless of weight, a principle that would later become known as the law of free fall.

Although some historians debate whether the experiment truly took place this way, Galileo’s writings confirm he studied falling objects in great detail. Whether or not he dropped them from the famous tower, Galileo’s ideas marked a major turning point in science. He used experiments and observation, rather than relying solely on ancient texts, setting the stage for modern physics.

Galileo’s Stand on Trial for Upholding Science:

Based on his observations and other astronomers’ discoveries, no one could genuinely contend anymore that what was seen through the telescope was merely an optical illusion rather than a true depiction of reality. The sole argument left for those who would not accept the conclusions initially put forth by Nicolaus Copernicus, a mathematician and astronomer from the Renaissance period, and supported by a growing body of evidence and scientific rationale, was to dismiss the interpretation of the findings. Theologians came to the conclusion that the Ptolemaic geocentric model, which had become the orthodoxy of the Catholic Church, and literal interpretations of scripture were at odds with a moving Earth and a stationary sun.

Galileo on Trial: The Clash Between Science and Faith:

In 1632, Galileo published a book titled Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, where he explained his ideas. But Galileo didn’t just present his arguments; he mocked those who still believed that the Earth was the center of the universe. This did not sit well with the Church, which held the belief that the Earth was stationary and at the center of everything. Pope Urban VIII decided that Galileo had gone too far, so he ordered the chief inquisitor, Father Vincenzo Maculano, to put Galileo on trial.

On April 12, 1633, Galileo’s trial began. It would be held in three sessions, on April 12, April 30, and May 10. In the first session, Father Maculano reminded Galileo of a warning he had received 17 years before. At that time, the Church’s Commissary General had told Galileo to give up his belief in the Copernican system and to never teach or defend it. This was a serious reminder, as Galileo had indeed continued to write about Copernican ideas, even if he added a few words suggesting that there might be room for doubt.

When asked to recall the warning, Galileo told the court that in 1616, Cardinal Bellarmino, a high-ranking Church official, had told him he could think about Copernican ideas as an interesting theory, but he must not believe in them as absolute truth. Galileo even brought a letter from Bellarmino as proof of this more lenient instruction.

Legally, this letter complicated things. The original warning told Galileo he must not “hold, teach, or defend” the Copernican ideas in any way. But Bellarmino’s letter only said he should not “hold or defend” the ideas. This left room for interpretation—had Galileo really broken the law?

A special committee of church officials was then called to review Galileo’s book and see if he had crossed the line. They concluded that he had. One of them, a Jesuit named Melchior Inchofer, went further, saying that Galileo clearly “believed” in the Copernican model and wasn’t just discussing it hypothetically.

Galileo was deeply shaken and, fearing for his life, admitted that his book might have made the Copernican ideas seem stronger than he intended. He blamed this on “ambition, ignorance, and carelessness” and offered to correct anything the court wanted. He also begged for mercy, considering his age and failing health.

Unfortunately, a summary of the trial included some false accusations that painted Galileo in an even worse light. There was a rumor from years before that Galileo had said something insulting about God, which was untrue, but it was included in the report anyway, making him look like an even greater threat to the Church.

On June 22, Galileo’s sentence was delivered. He was found guilty of heresy and was forced to renounce his support of the Copernican system.

Galileo’s Final Stand: A Scientist Silenced and a Poet’s Warning:

On June 22, 1633, Galileo was brought before the court. He was forced to kneel as he listened to the charges against him. The Church declared that he was “vehemently suspected of heresy” for supporting the idea that the Earth moved around the sun. Galileo had to publicly abandon his belief in the Copernican model and read a statement denying much of what he had worked for his whole life.

From the Church’s point of view, they believed they had acted within their rights. Galileo had broken two clear rules: he had written Dialogue, a book defending the Copernican model, which went against a direct order given to him in 1616 not to do so. And when he asked the Church for permission to print the book, he had failed to mention this earlier order.

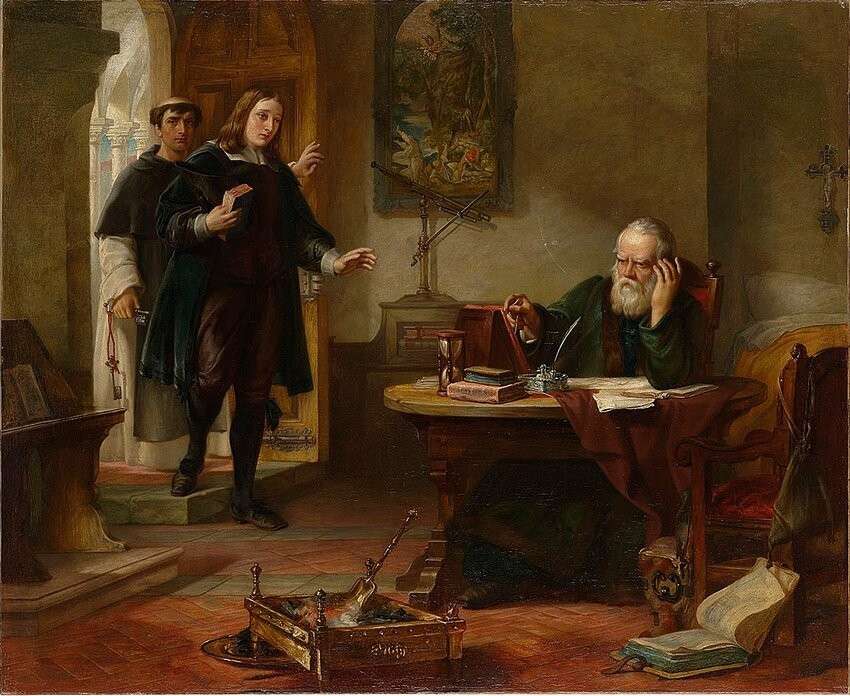

Five years later, in 1638, Galileo was an old man under house arrest. By then, he was also blind. That year, a young poet named John Milton came to visit him. Milton was deeply affected by what he saw—a once-great scientist now a prisoner for his ideas.

Years later, in 1644, Milton spoke to the English Parliament against censorship and licensing. He mentioned his visit to Galileo and warned that Italy’s greatest thinkers were being silenced by fear.

He said that nothing valuable was being written in Italy anymore, only empty praise and foolishness. He shared that he had met the “famous Galileo” as a “prisoner to the Inquisition, for thinking in Astronomy otherwise than the Franciscan and Dominican licensers thought.” Milton’s words would live on, reminding people of Galileo’s struggle for truth and the dangers of silencing new ideas.

Death:

In the quiet of his home near Florence, Galileo Galilei spent his final days under house arrest, Blind, elderly, and weakened by illness, he continued to work in secret, still passionate about science despite his failing health. In his final days, he suffered from a fever and heart problems. On January 8, 1642, Galileo passed away at the age of 77.

Although Galileo died as a prisoner, his ideas lived on, sparking a revolution in science and inspiring future generations to question, explore, and seek the truth—no matter the cost.